COVER:

Is this work of art by Colin Quashie inflammatory or does it only tell the truth?

Censored

by Chris Haire

According to Janie Askew, the executive director of Redux

Contemporary Art Center, there are three feelings that viewers might

experience when they're confronted with one of Colin Quashie's works:

First is mirth, then guilt, and finally sadness. We agree with Askew.

After all, we here at the City Paper experienced these exact same

emotions when we first saw Quashie's biting, satirical pieces.

From "Rainbro Row" to "Black People Love Pork Because Africa is

Shaped Like a Pork Chop," the local contemporary artist has plenty to

say about race, America's shameful past, and our future. And time and

time again, he does so in the cleverest — and most uncomfortable — ways.

Which is why we chose to run Quashie's "Slaveship Sardines" on the

cover of this week's issue.

However, after much debate in the City Paper offices over a single

word on this image, the decision was made to cover it up. Were we right

or were we just being overly sensitive? Is it time to finally discuss

America's past in its entirety or should we just try to forget it?

Scroll down and judge for yourself.

ARTICLE:

Colin Quashie's pointed response to the world around him

Op-Ed Art

by Susan Cohen

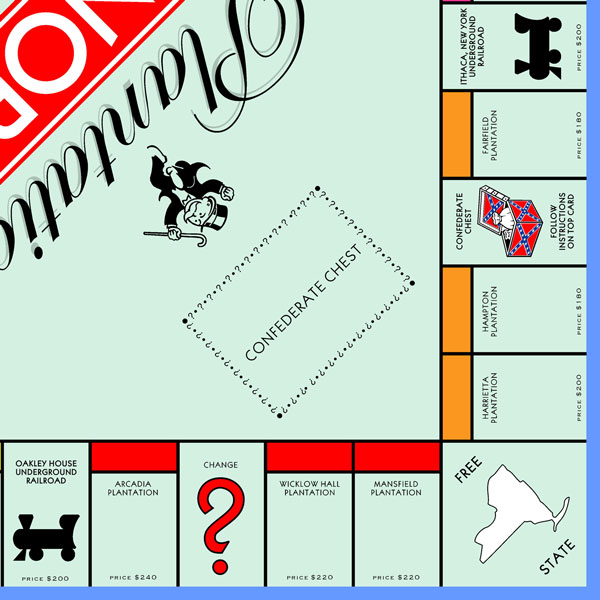

Plantation Monopoly is a board game that viewers will be encouraged to play during the exhibit's run

It may be difficult to spot Colin Quashie's second-story studio if you

aren't explicitly looking for it. An indistinct C and Q pasted to a

glass door are the only clues that something else goes on in this

standalone brick-and-concrete building on Upper King Street besides the

haircuts that take place in the first-floor barber shop. It doesn't help

that the logo gives a better impression of a cloud than a formal set of

initials, the puffy and bulbous letters joined together in a cartoonish

fashion. So instead, a better sign of what happens on the second story

may be in the downstairs shop, where one of Quashie's works hangs on a

wall near the wide windows.

Upstairs, you may hear quick and cool jazz, with the occasional

overpowering spurt of gospel coming in from below. When the artist

acquired his space a little more than two years ago, the hair cuttery

was an accountant's office.

Inside, the studio is a wide, tidy room, anchored by a coffee table

surrounded by a handful of wicker chairs. Venture too far from this

oasis, and you might bump into a more than six-foot-tall accordion-like

birch panel advertising an alternate universe's housing development or

brush against a framed poster leaning on a partition. Quashie has no

gallery representation, so this space offers an unofficial retrospective

of his decades-long career. During the 20 or 30 hours a week the artist

typically spends here, the studio has played host to MFA classes and

arbitrary visitors, sometimes more than a dozen at a time. Someone

familiar with his body of work can delight in spotting Quashie's

signature characters on his walls, like his appropriation of Charles

Schultz's Franklin, the token black character of Peanuts.

When a show of his closes, no matter how notable, Quashie usually takes

his work home with him. He doesn't sell many — or really any — of his

compositions. His art is not something you can inexplicably hang in your

living room; Oprah's grinning face on a ruby-red box of Auntie Jemima

pancake and waffle mix probably wouldn't match many sofas, and his

tourist-poster spoof "Rainbro Row," with its vividly painted slave

cabins, would make little sense in a sunny, white-washed vacation home.

Other work is less tangible, like the "blackbored," a chalkboard he

often installs in show spaces; he'll have it set up in the foyer at

Redux Contemporary Art Center, where his show The Plantation (Plan-ta-shun)

officially begins a run on March 30. Or the exhibit's signature board

game, Plantation Monopoly, complete with deeds, paper money, and slaves

and mules up for sale.

Like many of his peers, Quashie has taken the time to craft an artist's

statement, but this type of work doesn't require an esoteric explanation

of its greater purpose. It is about race. It is political. It is

emotional. Even in its best moments, it can be garish and aggressive,

impeccable in its delivery but uneasy in its message. It is meant to

start a conversation, and, for better or worse, it does.

And that message surges from an unassuming man in glasses, who on our visit is wearing a T-shirt, jeans, and a baseball cap marked with the "F" and alligator of the University of Florida, the college he attended for a few semesters. Quashie is a former Navy man, comedy writer, and Emmy Award-winner. He lives on Carolina Street with his wife of 11 years, Cathy. He has two stepdaughters and two grandkids. He wakes up at six every morning and drives Cathy to work, then spends a few hours planning, catching up on paperwork, and writing — he has a short film that's currently being shot in Atlanta — before doing what helps pay his bills: maintenance work, like installing ceiling fans. It gives him flexible hours. Then he'll spend his afternoons in this studio, sometimes working well into the night if he's deep into a specific piece.

Most remarkably, Quashie is a Charleston artist who hasn't exhibited a

solo show in the city since 2005. "He is among the best artists working

anywhere today, but most people in Charleston have no idea what he

does," says Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art Executive Director Mark

Sloan, who has known and worked with Quashie since the early '90s, and

who has dealt with the controversies that come as a result of an

inflammatory Quashie show.

"I call it anger, not that I'm angry," the artist says of his

motivation. "I always hate using the word anger because people never

seem to understand it. They always think, you know, you're the angry

black man. No, no, no. It's not that at all." Instead, he likens his

aesthetic to Bob Dylan writing an anti-war song. "This is my op-ed. This

is basically what it is. Art is my op-ed. It is how I respond to

things, and that's what I'm passionate about — responding to things

around me that make an impression on me."

Quashie wants to add to the dialogue, to have a conversation, and to ask

questions. It just so happens that he does so by producing a

mixed-media sculpture of Africa-shaped pork chops encased beneath the

Piggly Wiggly mascot, a provocative version of the kind you'd buy at the

grocery store for $3.55.

When the City Paper met with Quashie a few weeks ago, many of the works that will be featured in Plantation

still littered his studio. As he flits around the space, brainstorming

new ideas about whether to hang pages from a notebook or where he may be

able to find miniature atomizers for cologne samples, you get the sense

that parts of the show may still be a work in progress.

"This is the first time in my art career that I've ever put together a

cohesive show," he explains. "I usually do one to two or three or four

pieces, and then I move on to something else, because I guess I'm more

of a journalistic or social commentator of sorts. So whatever kind of

strikes me at the moment is what I work on. All of this could possibly

change within another two months and I could be on to something totally

different. It's just that I noticed that recently a lot of the pieces

I've been working on seem to have a throughline, and the throughline

seemed to be the plantation."

Redux's then-executive director Karen Ann Myers initially contacted

Quashie last spring about hosting the show. "I sat with Colin on the

panel for the Under the Radar exhibition [a collaborative show

between the City Gallery and the Halsey], and it reminded me how

powerful his artwork is and how important his voice is for the city and

the region," she says. "The city of Charleston is famous for celebrating

its history, for good reason, but in fairness, the story is complex,

and it should go without saying that that complexity deserves our

attention and recognition."

Plantation is not about slavery. As Quashie says, no one, black

or white, wants to talk about slavery. Instead, the show deals with

different aspects of plantation life, the pros and the cons. Ultimately,

it is about the past and the present.

"Charleston is so much about the past," Quashie says. "The South

basically glorifies the past. As far as they're concerned, the past

isn't the past. It's still the present. So that's what we market, that's

what we sell, but we do it in a lot of different ways, and plantations

are a mirror of that. Plantations are in the present, but they reflect

the past, and depending on your sensibilities and the way you look at

the plantation system tells a lot about what your sensibilities are."

Quashie's vision is nothing like the modern money shots of hanging moss

and white weddings you'll see on decadent blogs or in a luxury magazine —

his is harsher and truer to their dark history.

For each new piece produced for the show, Quashie took a part of that

past and connected it to something the audience will know from the

present. The gallery's outer wall has already been painted to ape the

Parker Brothers' game, with the massive outdoor artwork reflecting the

smaller version he has produced for the exhibit. Redux's mural has been

labeled with the familiar blue and green rectangles that signify the

game's most expensive properties, but Boardwalk and Park Place have been

replaced with Magnolia Plantation and Boone Hall. The playable

Plantation Monopoly will be set up inside, and Quashie sincerely hopes

he'll come in some time during the show's more than month-long run to

find patrons actually playing it.

"It's the exact same game, except that everything has just been

reconfigured," he says, but certain adjustments have been made to

reflect familiar Charleston landmarks and historical concepts. "I even

rewrote all of the rules and everything like that. And of course,

instead of hotels, once you get four slaves, you can buy yourself a mule

to work on your plantation." There's "Change" instead of "Chance," and a

Confederate Chest. Mr. Moneybags is still a central character,

rewarding players with $100 if their slave mistress gives birth to

mulatto twins. Instead of going directly to jail, you must pray for

abolition in a Quaker church, and the railroad system is of the

underground variety.

It might be a bold move for the gallery to give Quashie such a public canvas, considering that The Black American Dream,

his show for the 1996 MOJA Festival, was brusquely relocated at the

last minute, with a security guard installed outside to protect the

prying eyes of youth from Quashie's expression about a black person's

feelings of mediocrity compared to the white man ("Black is ignorant.

Black is lazy."). Luckily, Redux has given the artist free rein.

"Because we are a nonprofit, we are not limited by the saleability of

work, therefore our artists are allowed to experiment and push

boundaries," says Janie Askew, Redux's current executive director.

"Colin thrives in this type of environment. He is certainly not one to

be limited."

When guests of the show first walk into Redux, they will be welcomed

into a mini-classroom, complete with a wooden desk-chair and the

installed blackbored. In previous shows, Quashie has posed questions

like "George Washington is often referred to as the 'father of our

country.' So ... why are there no white people with the last name,

Washington?" This time around, he ponders, "If slavery ended so long

ago, it has no impact on the present. But there are people yet living

who knew someone who was either a slave or a slave owner, then ..." (The

City Paper has taken some liberties with punctuation, as the quote was spoken to us and not read directly off the blackbored.)

Visitors will be encouraged to write their responses to the query in a

spiral-bound notebook, which Quashie keeps for himself at the end of the

show. Today, the artist flips through pages from a previous blackbored,

one inspired by Dr. Laura Schlessinger's racist blowup in August 2010,

and the N-word litters the replies in all sorts of bubbly, slanty, and

sloppy handwriting. Quashie goes through these answers and decides on

the one that is most correct, though no one is truly ever correct. The

closest gets a free print.

As they continue into Redux, visitors will see screenprints, acrylic

paintings, mixed-media, and more. Quashie is a rare artist who balances

quality and quantity, and as impressive as his ideas are the many ways

he chooses to express them. "I have no mediums. I refuse to restrict

myself," he says. "I refuse to allow myself to be static when it comes

to any one particular medium. I don't understand why artists do that. It

just makes no sense to me whatsoever. One of my favorite quotes is an

old Abraham Maslow. It says: 'If your only tool is a hammer, you tend to

look at every problem as a nail.'" He doesn't think you can address

every particular subject in the same exact way — different topics

require different tools. "Sometimes I have to do it as a coloring book.

Sometimes I have to do it as just words or maybe an oil painting or

something."

But whether he wants to hit the viewer over the head with an idea or use

a bit more finesse, he almost always utilizes advertising and other

forms of modern iconography. "Then your battle is already half done. Why

reinvent the wheel?" he asks. "All I have to do now is just tweak it,

and not comedically or anything like that — real life."

In Plantation, a timecard stands tall, marking the long hours a

slave would work each day, including weekends. The brochure for

Plantation Properties takes descriptions from a modern housing

development to detail the amenities of slave cabins. Plantation palettes

offer color samples, like Whip-or-Will and Bar-B-Crew, for your

mansion.

Another piece uses text straight from old fugitive slave posters, only

the word "Reward" has been changed to "Resumé." And a plantation

magazine, complete with an editor's note, offers a sample of Mandingo

cologne and advertisements for Fledex and J. Crow clothing. (Quashie

once envisioned a show conceptualized around a department store, with

real clothing produced for his J. Crow brand. He promises that any

connection to the well-known J. Crew is purely accidental; it took a

friend to point out the connection between the fictional brand and the

nonfictional one for Quashie to even realize it).

And there is a different part of Plantation, once you pass

through the images of scarred backs and burning bodies, to another

section of the gallery. It is a softer side, both in meaning and in

presentation, with pieces in gentle colors, paintings that will temper

the volume of Quashie's louder works.

"I realized I was kind of getting out there a little bit as far as the

cynicism was concerned, and so I wanted to pull it back in, because the

bottom line is I also wanted to talk about who were the real people who

lived on these plantations," he says. Quashie found photographs of

former slaves, now left to their own devices in an unfriendly world, on

the Library of Congress' website, and he wanted to make them larger in

life. In one painting, a man poses in a slightly crumpled blue suit, a

white beard decorating his tired face, his wife and home in

black-and-white behind him.

The plain background is meant to represent the past. The colorful subject is the future.

There was a time when Colin Quashie was a commercial artist.

When he started in the 1990s, his work was available in galleries, and

people bought it. He did fairly well, but it wasn't his style. He was

doing derivative stuff that he knew would sell, and at one point he even

got a commission for some wildlife work. "You already saw the path that

you were on," he says. "It's either you are going to stay on this path,

or get off now. Hurry up and get off right now. So I jumped off.

He was also working at a gallery at the time, and he bore witness to the

power play between dealers and the dealt. Like, "This sold. Can we get

two more like it? Someone's asking you to do this."

His peers would do as they were told. "And I'm like, wow. That's a job.

It's like the passion has been sucked out of you and now you're just

servicing the market," he says. "I can't allow my art to go in that

direction. I won't allow it to. That's never, ever, ever, ever going to

happen."

Still, he needed to find something that he was passionate about. And when he created his "EBONY

Magazine (Issues Ir-relevant to Black America)" piece, a cartoon

mock-up that stands out in bright yellow on a wall in his studio, he

says that's when the clouds parted.

As a result of his epiphany, Quashie rarely sells his work. He is not a

commercial artist and has no intentions of ever becoming one. "People

don't want this crap on their walls," he laughs. He does sell a piece

every now and then, and he's starting to get more inquiries. He's also

searching for a new art agent. "I just don't want to be Mr. Poster. It's

just too personal to me, and I don't want to have to service the

machine.

But that's not to say that he's never gotten a lucrative commission —

last year, he was recruited by actor Laurence Fishburne to create a

portrait of his wife, actress Gina Torres. (You can see it on Quashie's

blog, quashieart.blogspot.com).

Nevertheless, Quashie has turned down other offers, because he's not

going to paint your dog. "I don't want my art to become my job. It's my

passion, and if I can sell my passion, then that's fine, but if I can't,

then I'll just continue doing what I'm doing. I work as a maintenance

man now to pay my bills. And if I never sell a piece of artwork again,

then so be it," he says.

In the meantime, he has his daily job, plus freelance design work, and he teaches at Charlotte's Innovation Institute

four or five times a year. He may have to work outside of art to pay

his bills, but it gives him time to mentally construct, analyze, and

plan for upcoming exhibitions, including four more this year.

"Eventually, I do want my passion to become my job as something I can

earn a living from, just not a job as in a chore."

Quashie doesn't criticize the gallery system, because galleries are

businesses. Personally, he's afraid of becoming a commodity. "Once you

fall into the gallery system, you're kind of at the hands of what people

are willing to purchase." That's why he's gone through a number of art

agents: They were trying to sell the art, not the artist. "Once you

start following that ship, you get off track of what it is you're

ultimately trying to accomplish. Sometimes there's no going back. Once

you get known for painting red, it's hard to shift over and tell people

'I really, really like painting blue.'" Quashie doesn't ever want to be

expected. He wants to be anticipated.

And Plantation surely accomplishes that. Both the artist and

Redux have received nothing but positive response to the show, which

could be due to the scarcity of such an opportunity. If Mark Sloan had

his way, Quashie would have a show at the Whitney Museum of American Art

in New York City. "His work is that caliber, but there are many

intermediate steps that need to take place in order for that to happen,

but I predict it will, and soon," he says. "Quashie is a nationally

significant artist that happens to live in Charleston. I think his work

offers a scathing critique of America. His voice is strong, his ideas

provocative, and his message is essential."

And yet you're never going to be able to stroll through the French Quarter and stumble upon one of his pieces. When Plantation closes, it might be a long time before we see such a breadth of material from Quashie in Charleston again.

Regardless, considering Quashie isn't a frequent celebrity on the local

First Friday circuit, the city's art scene is certainly one that he's

proud of. "I brag on the Charleston contemporary art community," he

says, crediting figures like Sloan and spaces like Redux and the Halsey, as well as Rebekah Jacob Gallery and Robert Lange Studios.

"Ten, 15 years ago, that wasn't the case," he says. "My god, it was

dead. This place was horrible. It was run by the watercolor society, it

seems like it, the watercolor and the poster artists. This was the place

where contemporary art went to die."

Sadly, he can't boast about a community of contemporary black artists in

the same way. He's not saying they don't exist, but he's not personally

aware of them.

There may be three stages of reaction to a Colin Quashie piece, as Janie

Askew describes. First is mirth, in the form of laughter. That is

followed by guilt, which in turn is followed by sadness.

"I stand by the fact that contemporary art is not always easily

digestible for the masses," she says. "The best art invokes emotions and

thought. Colin's work just so happens to be provocative, and I am proud

to be affiliated with an art organization that supports that.

Unfortunately, it can be a quick jump from provocative to offensive,

depending on the eyes of the beholder. Quashie's work used to upset

people. "That was my fault," he admits. "I used to make a lot of

statements in my artwork. I used to use my artwork as a sounding board

by which to make statements, and I realized that that was wrong. You

can't do that. You can if you want to, but you're more effective by

asking someone a question rather than telling them a statement." Quashie

had to learn how to take himself out of the equation. That doesn't mean

he's not present in his work, but he is more objective in the way he

approaches it.

Most importantly, he started painting facts, not truth. "I got rid of

truth. Truth will get you in trouble, because truth is subjective. Ten

different people, that's 10 different truths. Ten different people,

there's only one fact." It's a lesson he learned from the comedy writing

he did in the '90s for MadTV and other shows. You can lay out

the truth, and just tweak it a little bit. The way that he chooses to

articulate that one fact is where things can get subjective, but you

still can't argue with the facts. Every little detail on his Monopoly

board is a fact. So if someone gets upset, there's no blow-back on

Quashie. That's something the viewer is dealing with, something internal

that they're pissed off about.

Still, criticism still comes in from all across the board, black and

white, young and old. "People are so nonsensical sometimes in what their

passions are," he says. "You can't call it. You really can't. And I've

given up trying." He was once cursed out by a black woman who told him

he needed to be more responsible to his community. Benedict College, a

historically black school in Columbia, shut down a show over a massive painting of Jesus Christ on the cover of CQ magazine.

Its teasers questioned conservative backlash to gay culture,

advertising stories like "Nature, Nurture, or Nomenclature? 'Can a man

be born (again) gay?'" The college thought he was promoting

homosexuality.

Once, an elderly white woman in Orangeburg called him a racist to his

face. "But the fact that she stood there and came to me ... you have to

respect that," he says. "We actually had an incredible conversation."

He'll be able to hear direct responses to Plantation at a panel

discussion at Redux on April 7 at 3 p.m., entitled "Idea and Meaning in

the Art of Colin Quashie." It will be moderated by Frank Martin, a

doctoral scholar in the African-American Professors program at the

University of South Carolina who curated an exhibit with Quashie in

2005. The artist is not actively participating in the panel, but he'll

be in the audience, bearing witness as people like Mark Sloan interpret

his work.

"Miss Margaret" is a work in progress, a lovingly vivid portrait of a

neighbor of Quashie's that stands incomplete in the front nook of his

studio. At first, he wanted to compose her out of charcoal. "I like the

look of charcoal, but I can't stand the tactile feel of charcoal. I hate

it. I hate that dusty shit," he says. So instead, he painted the canvas

in a solid tone to create a kind of colored paper, and he's in the

process of painting over this base with oils to get the same kind of

appearance as the powdery medium. Miss Margaret will be part of "Faces

of Color," the new direction that Quashie is heading into.

"I'm starting to repeat myself, which is something I absolutely refuse

to do, I hate doing. I can't stand it," he says. "I may paint something

two or three times, then it's time to move on. I've done that. Let's

keep going."

"Miss Margaret" is a sensible evolution of the portraits that will hang

in the back of Redux, and a much gentler interpretation of Quashie's

overall goal of addressing issues of race. While this painting and the

one he has hanging in the barbershop below him may not be so blatantly

argumentative, they still manage to address his issues with race. But,

"Don't worry. There's more cynical stuff coming," Quashie tells us.

"I just want a dialogue. I just want people to gather information," he says of Plantation.

"There's a lot of people in this city who may look at plantations from

one perspective and one perspective only, and I want them to be able to

come to this exhibition and to look at them and say, 'Oh, I didn't

realize that.'" He hopes that a nudge from his work can lead to a

greater discussion. "I guess they can have that conversation in the way

that they choose to approach things, in the way that they think about

things, to take other people's perspectives into question sometimes.

That's something I do as an artist. Before I paint anything, you always

have to weigh the pros and the cons ... And that goes a long way, when

people do that in every facet of life."